Structured teaching

Research summary

This project evaluated the effectiveness of two elements of structured teaching – visual schedules and work systems – in inclusive mainstream classrooms. A program for visual schedules and work systems was piloted, trialled, and evaluated with Australian teachers.

Structured teaching is a well-established framework that can support students on the autism spectrum to stay on task and move between tasks. It originated from the Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) program in the 1960s.

Research aim

This project was divided into three phases. Each phase had its own aim:

- Phase 1 aimed to refine a structured teaching program from the original teacher workbook (TEACCH) for use in mainstream classrooms and establish a method for evaluating the program’s effectiveness.

- Phase 2 aimed to investigate the effect of visual schedules and work systems on students’ on-task behaviours and productivity, and on the independence of students on the autism spectrum when a mainstream teacher implemented these strategies for the whole class.

- Phase 3 aimed to obtain feedback from mainstream primary school teachers on the utility of visual schedules and work systems in their classrooms.

Key elements

Structuring the physical environment supports students’ sensory and executive functioning needs by adding meaning and context.

Structure the physical environment of your classroom by:

- clearly defining areas for activities

- clearly labelling and positioning materials

- minimising auditory and visual distractions

- arranging seating according to the individual needs of students, e.g. providing physical space around desks; seating students where they work best – near the teacher, near the classroom door, at the back of the classroom

- providing a sanctuary space

- using routines.

Using visual cues in schedules helps students to sequence predictable events, and helps teachers to give students notice of anticipated changes and encourage independent transitions.

Include visual cues in your schedules by:

- displaying and using weekly schedules

- providing individualised timetables

- using pictures and photographs on schedules

- sequencing the visuals so that the order is easy to understand, e.g. ‘first, then’ or ‘what next’.

Visual and physical cues used in work systems help students to understand:

- what task or activity they are expected to complete

- how much work they have to do and how much time they have

- if they are making progress on a task and when it is finished

- what they should do next.

Implement visual and physical cues in work systems by:

- individualising work systems according to what students need, e.g. working from folders or putting work in baskets

- presenting numbered tasks on the left side of students’ desks and having students place finished work on the right side

- presenting work systems in folders with left-to-right organisation and itemised tasks

- making tasks easy to follow by breaking them down and organising them visually.

Visually structuring your classroom helps to present information with visual clarity.

Use visual structure in your classroom by:

- using text or images to convey rules or instructions

- organising materials to make their function clear

- using white space to clarify instructions

- implementing colour-coded systems.

Additional information

For teachers:

Visual schedules and work systems were shown to increase the on-task behaviours of students on the autism spectrum.

Visual schedules and work systems can be implemented in mainstream classrooms using a variety of pictures, symbols, and technology.

For professionals supporting teachers:

How these strategies are conveyed to teachers is important and will determine:

- whether they are implemented

- how effectively they are used.

If adaptability is incorporated in the design of an intervention, mainstream school teachers are more likely to adopt the intervention as part of their everyday practice.

Quick reference guide

Structured teaching: Quick reference guide

Check your fidelity

fidelity

noun

- Faithfulness to a person, cause, or belief, demonstrated by continuing loyalty and support.

- The degree of exactness with which something is copied or reproduced.

Why did the project team develop checklists?

When an intervention is effective in one classroom, the same result can be expected in another classroom if the intervention is used with fidelity.

Researchers from Autism Queensland developed a checklist to support teachers to implement visual schedules and work systems as they are intended to be used. Teachers can use the checklist to monitor that their use of visual schedules and work systems has high fidelity.

Structured teaching: Checklist for teachers

Our evidence base

What was the aim?

Phase 1 of the project aimed to identify and explore issues experienced when using the original teacher workbook from the TEACCH program to implement visual schedules and work systems in mainstream classrooms.

What did the project team do?

- The team used a single-case study methodology in a mainstream classroom.

- The teacher implemented structured teaching using the original teacher workbook from the TEACCH program.

- The team investigated social validity: Did the teacher and the students think that using structured teaching was helpful?

- The team investigated implementation fidelity: Could the teacher use structured teaching in their classroom?

Where was Phase 1 of the project conducted?

Phase 1 was conducted in regional Queensland.

What did the project team find?

- The teacher needed more information in the original teacher workbook than was provided.

- The student reported that the timetable was of some help and that their work system was very helpful.

- The teacher reported that the timetables were easy to use and that work systems helped keep many students on task.

- The teacher reported that developing task checklists (in the work systems) to suit all students in their class took time.

What was the aim?

Phase 2 of the project aimed to investigate the effect of visual schedules and work systems on students’ on-task behaviours and productivity, and on the independence of students on the autism spectrum when a mainstream teacher implemented these strategies for the whole class.

What did the project team do?

- The team used a multiple-baseline single-case experimental design in four mainstream classrooms.

- Each teacher received an amended teacher workbook and additional guidance from the team.

- The team worked with the teachers to define the on-task and off-task behaviours of each of the four students on the autism spectrum.

- The team measured the effects of visual schedules and work systems by observing and recording on-task and off-task student behaviours before and during implementation of the strategies.

- To measure productivity, the team recorded the number of words the students wrote before and during the above strategies.

- To measure independence, the team recorded the number of prompts that students needed before and during the use of the above strategies. The team assumed that students who worked more independently would require fewer prompts.

- The team used a fidelity implementation checklist to evaluate whether the above strategies were implemented according to the original teacher workbook guidelines.

Where was Phase 2 of the project conducted?

Phase 2 was conducted in four classrooms in regional Queensland.

What did the team find?

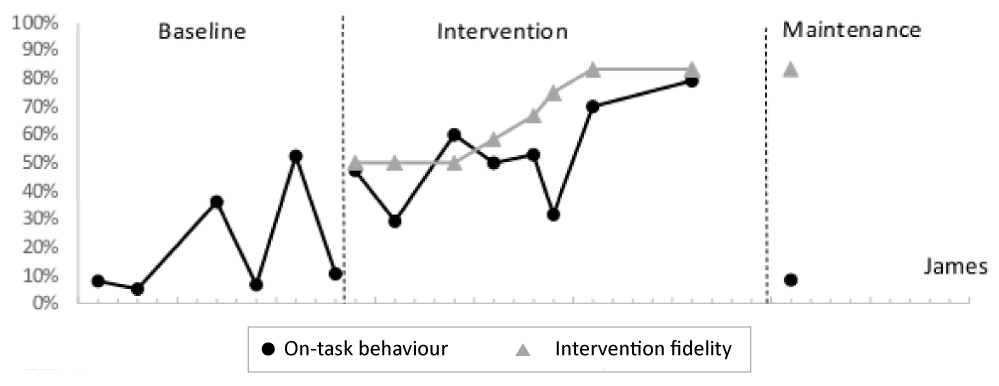

- All four students were on task more often when visual schedules and work systems were used. The increase in on-task behaviours was statistically significant for three of the four students.

- For one student, on-task behaviour increased from 20% before visual schedules and work systems were introduced to 53% after they were introduced. After the visual schedules and work systems were removed, the student’s on-task behaviour dropped to only 8% (see Figure 1).

- The frequency of off-task behaviours did not change in any significant way when visual schedules and work systems were used.

- Two students showed significant increases in productivity.

- No change to independence was recorded for any students.

Baseline

A minimum of five observations over a 2-3 week period to establish a baseline of behaviours. Ten second partial interval coding was used. Student on- and off-task behaviours and teacher prompting were measured from the start of the task. Coding reliability established.

Intervention

Teacher met researcher to discuss the workbook (Haas, 2015). Teacher implemented appropriate elements of structured teaching.

Maintenance

Only implemented for one student

What was the aim?

Phase 3 of the project aimed to obtain feedback from mainstream primary school teachers on the utility of visual schedules and work systems in their classrooms as presented in the amended program Finished! The On-task Toolkit (Macdonald & Haas, 2016).

What did the project team do?

- The team used a two-stage survey to evaluate teachers’ responses to the amended program. Forty-one (41) mainstream primary school teachers completed Stage 1 of the survey and 22 of those teachers also completed Stage 2.

- In Stage 2, the team used a qualitative case study approach to obtain further feedback from four mainstream teachers about the use of the strategies outlined in the amended program.

- The team used the above approach to capture the complex and rich experience of implementing the amended program.

Where was Phase 3 of the project conducted?

Phase 3 was conducted in classrooms across New South Wales, Victoria, and Western Australia.

What did the team find?

- The teachers’ responses to the amended program were overwhelmingly positive – they found it easy to follow and useful.

- Reading the amended program increased the teachers’ confidence but not necessarily their knowledge about visual schedules and work systems.

- All four teachers had some level of success and affirmed they would continue using the strategies with their whole classes.

- The teachers were able to describe independent delivery of visual schedules and work systems as part of their everyday practice.

Research snapshot

Structured teaching: Visual snapshot

Meet the researchers

Dr Debra Costley

Ms Kaaren Haas

Professor Deb Keen

Dr Satine Winter

Dr Jill Ashburner

Dr Elizabeth MacDonald

All researcher details including names, honorifics (for example ‘Dr’), and organisational affiliations are correct at the time of the project.

Publications from this project

Articles informing this project

Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., & Rodger, S. (2010). Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behavior at school. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(1), 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.07.002

Banda, D. R., & Grimmett, E. (2008). Enhancing social and transition behaviors of persons with autism through activity schedules: A review. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 43(3), 324–333.

Banda, D. R., & Kubina, R. M., Jr. (2006). The effects of a high-probability request sequencing technique in enhancing transition behaviors. Education and Treatment of Children, 29(3), 507–511, 513–516.

Bryan, L. C., & Gast, D. L. (2000). Teaching on-task and on-schedule behaviors to high-functioning children with autism via picture activity schedules. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 553–567. doi:10.1023/A:1005687310346

Cihak, D. F. (2011). Comparing pictorial and video modeling activity schedules during transitions for students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 433–441. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.006

Dettmer, S., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., & Ganz, J. B. (2000). The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(3), 163–169. doi:10.1177/108835760001500307

Fage, C., Pommereau, L., Consel, C., Balland, E., & Sauzéon, H. (2016). Tablet-based activity schedule in mainstream environment for children with autism and children with ID. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, 8(3), 1–26. doi:10.1145/2854156

Giangreco, M. F. (2013). Teacher assistant supports in inclusive schools: Research, practices and alternatives. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 37(02), 93–106. doi:10.1017/jse.2013.1

Hall, L. J. (1995). Promoting independence in integrated classrooms by teaching aides to use activity schedules and decreased prompts. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 30(3), 208–217.

Howley, M. (2013). Outcomes of structured teaching for children on the autism spectrum: Does the research evidence neglect the bigger picture? Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, Oct, 1–14. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12040

Hume, K., Loftin, R., & Lantz, J. (2009). Increasing independence in autism spectrum disorders: A review of three focused interventions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1329–1338. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0751-2

Hume, K., Plavnick, J., & Odom, S. L. (2012). Promoting task accuracy and independence in students with autism across educational setting through the use of individual work systems. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 2084–2099. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1457-4

Hume, K., & Odom, S. (2007). Effects of an individual work system on the independent functioning of students with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1166–1180. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0260-5

Hume, K., & Reynolds, B. (2010). Implementing work systems across the school day: Increasing engagement in students with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 54(4), 228–237. doi:10.1080/10459881003744701

Hume, K., Sreckovic, M., Snyder, K., & Carnahan, C. R. (2014). Smooth transitions: Helping students with autism spectrum disorder navigate the school day. Teaching Exceptional Children, 47(1), 35–45. doi:10.1177/1098300709332346

Humphrey, N. (2008). Including pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream schools. Support for Learning, 23(1), 41–47.

Jimenez, T. C., Graf, V. L., & Rose, E. (2007). Gaining access to general education: The promise of universal design for learning. Issues in Teacher Education, 16(2), 41–54.

Kasari, C., & Smith, T. (2013). Interventions in schools for children with autism spectrum disorder: Methods and recommendations. Autism, 17(3), 254–267. doi:10.1177/1362361312470496

MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1993). Teaching children with autism to use photographic activity schedules: Maintenance and generalization of complex response chains. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 89–97.

Mechling, L. C., & Savidge, E. J. (2011). Using a personal digital assistant to increase completion of novel tasks and independent transitioning by students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(6), 687–704. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1088-6

Mesibov, G. B., Shea, V., & Schopler, E. (2004). The TEACCH approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Practices

Structure tasks using work systems

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- plan and organise

- build independence

- understand expectations

Use visual schedules

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- transition smoothly

- understand expectations

- learn new concepts

Use visual schedules (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- transition smoothly

- understand expectations

- learn new concepts