Overcoming Written Difficulties

Research summary

Some students, including those on the autism spectrum, have difficulty with tasks that require them to use persuasive writing. Students can have challenges with:

- fine motor skills

- perceptual demands of handwriting

- conceptual and language demands of written composition.

As part of this project, the research team designed an iPad app to help students in Years 4–6 to produce persuasive texts. The design of the app incorporated three evidence-supported practices that are effective for students on the spectrum, including:

- assistive technology using writing support software (see the Use technology to support written expression practice to learn more)

- self-regulated strategy development (SRSD; see the Supporting persuasive writing practice to learn more)

- peer video-modelling.

The project found that students who experience difficulties with persuasive writing can use support software and SRSD to increase their:

- amount of writing

- quality of writing

- motivation

- self-belief.

'I’ve wrote some more stories and I’m getting more confident.'

—A participating student

Research aim

The research team considered the following questions:

- How can a targeted support program be designed to teach and scaffold self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) instruction in mainstream classrooms?

- What quality and length of written composition do students on the autism spectrum produce when using:

- handwriting

- writing support software, supported by video-modelling

- SRSD with handwriting, supported by video-modelling

- SRSD with writing support software, supported by video-modelling?

- How effective is the fully scaffolded SRSD instruction app at helping students on the spectrum to overcome their difficulties in written expression?

- For whole-class teaching and learning in an inclusive classroom, do students on the spectrum and teachers perceive the app to be:

- effective

- socially relevant

- ecologically relevant?

Key elements

Written compositions are central to many classroom learning activities, formal assessments, and informal assessments. The ability to write persuasively:

- helps students to demonstrate learning

- communicates ideas

- is an important part of the Australian Curriculum, as students are regularly assessed on their persuasive writing through NAPLAN.

Assistive technology such as writing support software has several helpful features, such as:

- speaking the words as they are typed, known as text-to-speech

- word prediction

- a dictionary to clarify words as they are typed

- a vocabulary list that saves words and compiles a personal glossary for students.

Previous research indicates that assistive technology such as writing support software can:

- help to overcome issues with the physical act of handwriting

- improve spelling ability and sentence construction of students with writing difficulties.

The app designed in this research project used software that enables the use of writing support features such as word prediction.

Some students, particularly those on the autism spectrum, have difficulties writing and may:

- write vague or unclear statements

- create writing that is difficult to follow, i.e. has poor textual coherence

- create writing with weak structure.

In addition to generating ideas and structuring an argument, persuasive writing tasks also require students to:

- consider different points of view

- anticipate the reader’s perspective

- present ideas in a way that readers will find convincing.

The app designed in this research project incorporated the SRSD strategy ‘POW+TREE’. SRSD has been shown to help students with their writing by scaffolding conceptual idea generation and sequencing.

Video-modelling is an effective way to support the learning of all students in a mainstream classroom, including students on the spectrum. As an inclusive teaching strategy, video-modelling:

- presents information in a predictable and systematic way

- gains and keeps the attention of students on the spectrum

- is less socially demanding and is more intrinsically motivating.

In this project, video-modelling reduced the demand on teachers and was used as an engaging way to provide instruction to students in subjects such as:

- the functionality of Texthelp Read&Write software

- using POW+TREE steps.

The app provided examples of completed NAPLAN-modelled persuasive writing tasks using the POW+TREE steps.

'I like that it scaffolded them and took the role of having to model it away from the teacher because it was modelled already. This meant the teacher was freed up to go around and work one-on-one or with small groups.'

—A participating teacher

Quick reference guide

Overcome written difficulties: Quick reference guide

Our evidence base

Co-design phase

To gain a broad perspective of the design considerations of the app and videos, researchers co-designed the app and peer-modelled videos with:

- graphic designers and app developers

- adults and students (including some on the autism spectrum), primary school teachers, and one school principal.

Method

Participants

The research team gathered feedback on the initial prototype through focus groups and semi-structured interviews with:

- 17 primary school students, including four that were on the spectrum

- four teachers

- two adults on the spectrum.

SETTi framework

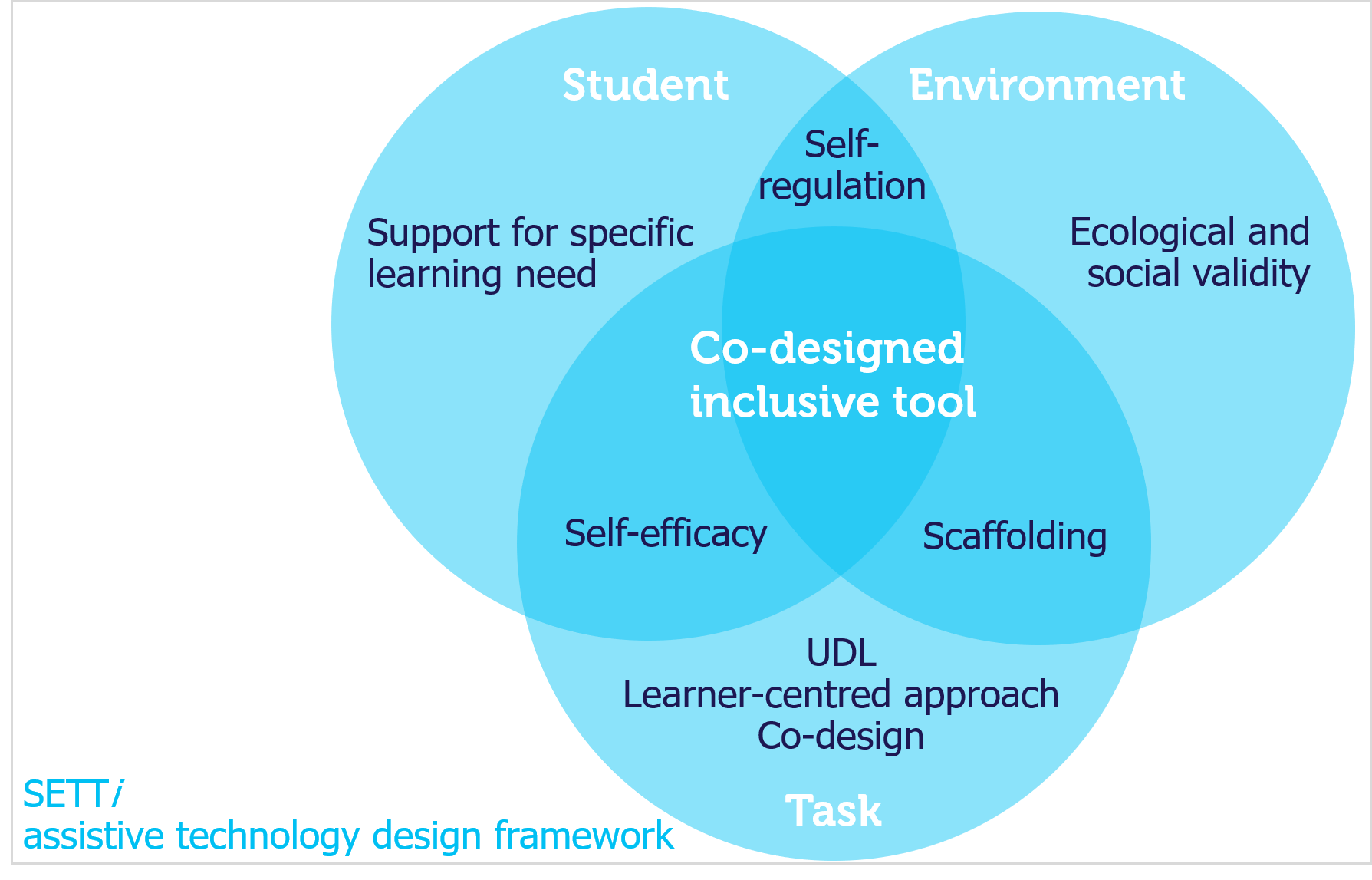

The research team modified the Student, Environment, Tasks, Tools (SETT) assistive technology selection framework. To recognise the inclusive, class-wide use of the co-designed app for this research, the team added an 'i' to the above acronym. The SETTi framework considers the needs of students, their environment, and tasks as a basis for designing and developing inclusive learning tools.

Scaffold components

Co-design of the app incorporated the ‘six components of scaffolding’ (Wood et al., 1976):

- development of learner interest in the task

- simplification of the task

- provision of encouragement and direction

- provision of critical feedback

- support to manage frustration

- modelling of a solution to the task

Co-design process

The seven-stage co-design process included:

- scanning and analysing currently available apps

- iterative prototype development and refinement

- co-design focus groups and interviews

- video development.

Overview of the co-design process

Results

The co-design process developed and tested the Power Writer app prototype based on participant feedback.

Evaluation of writing support materials

The research team investigated the efficacy of the Power Writer app by examining the quality and length of students' written texts when they used only:

- handwriting

- writing support software, which was explained using video-modelling by a peer

- SRSD with handwriting

- SRSD with writing support software, which was explained using video-modelling by a peer.

Method

Participants

Eight students on the autism spectrum in Years 4–6 participated in the single subject experimental design. Students attended mainstream primary schools in the Brisbane metropolitan area.

Design

A double-baseline ABAC design was used and each student completed a writing task with:

- A = handwriting (the baseline)

- B = writing support software alone

- C = the app for SRSD instruction.

The research team used this method to factor in any potential learning curve in the analysis and to determine the relative contributions of the writing support software and SRSD. If this study had only measured the impact of introducing both the writing support software and SRSD together, it would not have been possible to determine whether or not either or both strategies had affected written expression.

The first handwriting baseline (A1) was compared with the first intervention condition (B). Then, the second handwriting baseline (A2) was compared with the second intervention condition (C).

Materials

An Apple iPad Air 2 was given to each student, installed with Read&Write writing support software and the Power Writer app. Students also had access to wifi for both these programs.

40 NAPLAN-modelled prompt sheets were developed in consultation with two qualified markers, input from two children aged eight and 11, and review from teachers to ensure their suitability.

Results

Findings from the research team

- Writing support software significantly improved the writing quality of four students and the word count of two students.

- SRSD training provided by the app also significantly improved writing quality for one student and the word count of three students.

- All students had higher NAPLAN scores when using SRSD and writing support (condition C) than they did with writing support alone (condition B), with three students seeing a significant difference.

- Both students and teachers were positive towards the app components.

- All students continued using the writing support on the iPad during condition C, which may indicate their motivation to use the app.

- Students felt more positive about writing.

- Teachers reported improvements in the quality and length of students' written compositions, and their willingness to write.

Results demonstrated the complexity of the challenges involved in supporting the writing of students on the spectrum. The different support program elements and their effect on students’ writing performance were affected by the individual characteristics of each student.

Qualitative feedback

Surveys and semi-structured interviews, conducted both before and after the support program, provided qualitative feedback from students and their teachers about:

- student self-belief and attitude towards writing

- how students felt about using the various writing techniques, software, and strategies

- changes in students’ approach to structured writing tasks in the classroom

- attitudes towards the support program strategies and the acceptability of the app for providing writing support in inclusive, mainstream classrooms.

Student perceptions

Initially, all participating students expressed negative feelings about writing tasks and their self-belief in completing them. The students described writing tasks as hard, something that they were not good at, or something that took them longer to complete than their classmates.

Most of the students expressed a dislike for writing and had difficulty planning, conceptualising, and physically performing handwriting tasks.

Interviews conducted after the support project found that students:

- felt more positive about writing and had greater self-belief after the study

- achieved positive results using SRSD scaffolding in planning

- reported fewer handwriting challenges with the use of technology

- found the peer-modelled instructional videos particularly motivating.

Participating students said:

‘I’ve gotten used to writing and I’ve gotten help writing stories. I’ve gotten better at writing.’

‘I’ve actually started to write in class.’

‘That holiday story was really good. I was using persuasive words like, I mentioned that there was like this little cave…’

‘I’ve wrote some more stories and I’m getting more confident.’

‘I think the next time I am asked to do a persuasive text I'll be much better at it.’

‘It was quite boring doing persuasive texts. I hated them before I did this.’

Teacher perceptions

Six teachers completed surveys and reported that the support project was helpful for most of the students and that they were willing to recommend it to others.

Teachers reported improvements in the quality and length of students' written compositions and their willingness to write.

Teachers found the app to be:

- suitable for whole-class mainstream classroom use

- highly valuable in supporting struggling writers

- in need of further extension for competent writers.

Participating teachers said:

‘I can get a lot more out of Luke if he is using his iPad – I mean his stamina is higher. When he has to use a pencil, he just runs out of the will to write very quickly.’

‘The iPad just gives them that element. It takes the stress of using handwriting and the fine motor skills out of the equation and put what's actually in their head on the page.’

‘I would say that the iPad motivates them to get started and to continue working instead of dithering.’

‘His focus has incrementally increased and for longer periods since you started this research.’

‘I would say that is helpful with completion of the story. He'd make a start previously, and then get distracted and then to come back to it. I've read what he's written just recently and it's just flying ... the whole story is cohesive.’

‘I've got a couple of students who would really benefit from using SRSD. It's about organising their thoughts and all sorts of things.’

Ecological relevance

To assess the broader social validity of the project of the support program, it was trialled in selected classrooms, and focus groups were run with teachers who had used the program on a whole-class basis.

Method

Researcher observation of class use of the app

The class was shown two instructional videos and students were provided with materials before starting the writing task. Observations were made of the class as a whole rather than individual students based on the following prompts:

- How are students working? Are they working in groups or individually?

- Are students on task? Do students show interest in the activity? Are there issues with behaviour around staying on task?

- How is the app being used? Is the app being used as intended or in a different way?

- Do students appear to be engaged in the task?

- What questions or comments do students have about the app?

Teacher focus groups

The teacher focus group questions explored:

- teachers' opinions of the app as a tool for teaching purposes

- students’ responses to the video-modelling strategies

- student preferences for Read&Write writing support software compared to handwriting.

Results

Several themes emerged from the teacher focus groups and researcher observations, such as:

- self-belief

- self-regulation

- task management

- video-modelling

- inclusive use

- writing support software

- school environment

- future improvements.

Self-belief

The app engaged both mainstream students and students on the autism spectrum who struggle with writing self-belief.

Teachers said:

‘I'm assuming it's from the app that he was a bit more confident to put things down on paper.’

‘She's been more willing, not reluctant.’

Self-regulation

Teachers often mentioned the app and its ability to assist students with self-regulation and writing composition.

Teachers said:

‘It gave them a very clear direction and structure, directions for moving, and structure through the areas where they could actually write their ideas.’

‘I think they could see if it made sense and having the structure there took the pressure off them trying to remember that. They could focus on exactly what they were writing.’

Task management

Students working in groups were engaged and on task, and discussed the materials and chosen topic.

Teachers said:

‘I found that one of my students in particular has awful handwriting and fine motor skills and it’s difficult to read his writing and stuff. I noticed he was quite engaged because he didn't have that barrier for him.’

‘If they didn't like the app and videos they'd have been silly and mucking around. I think you could take it from that, that they were watching it and engaged.’

Video modelling

Students engaged with the instructional videos. However, some students needed help transitioning from the example videos into the writing task.

Teachers liked the peer-modelled videos and that students could watch them more than once to comprehend the information. Video-modelling enabled the teacher to spend more time supporting other students. Teachers also liked the relevance of video topics.

Teachers said:

‘I thought the videos were awesome.’

‘I think they could relate to it.’

‘I think that there were topics that appealed to them, like the gaming one and the other topics that were offered were great.’

‘I think because of the samples that were given, some of them did some really outlandish topics that they were discussing. One group that I was with wondered what would happen if we could all have flying cars and they were, you know, rattling out all these ideas.’

Inclusive use

The app encouraged collaboration among students, including students on the spectrum working with mainstream students. Teachers thought the app was useful as a starting tool for reluctant writers, and that more advanced writers needed extension.

Teachers said:

‘The students were actually conversing with each other about it, so I thought that was a plus’.

‘Competent writers need extension because they weren't pushed as much.’

Writing support software

Teachers considered Read&Write to be a useful tool but noted some limitations related to spelling assessment, lack of personality in the voice, and that text-to-voice could be distracting when used in a class environment.

Teachers reluctant to use Read&Write for English assessment were concerned about the misuse of the software by capable students.

Teachers said:

‘My students found, especially the ones that are reluctant writers and are not neat, Read&Write good because it was able to read back to them what they had typed in.’

‘I think Read&Write is great. My students who struggle with stamina, I think it gives them some tools to continue and help them with their writing even when it's difficult.’

‘You know, if they're using Read&Write all the time, there's never going be a spelling issue. So then how do you report on that?’

‘It repeated back every word they were writing, and then when they realised that, a lot of them were touching all these random words and then it was saying like gibbly gibbly.'

School environment

One of the most limiting factors associated with using inclusive technology in the schools was the availability of the infrastructure required to run it. Challenges with technology include:

- insufficient iPads for every student

- parents having to install the app on personally owned iPads

- lack of access or reliability of wifi in some schools

- lack of technology support and infrastructure

- unsuitability of an iPad app for schools that use other types of portable or desktop devices.

Teachers said:

‘Yeah, it's just the infrastructure, the technology.’

‘It would be awesome if it was made into a website, just for people that don't have iPads, because we do have one-to-one laptops.’

Future improvements

Teachers described the need for greater access to the student work, statistics on student work (e.g. progress reports), and the ability to incorporate teacher feedback. Teachers reported the app did not support high-performing students and needed variable levels of scaffolding. Both teachers and students would like a more engaging app that included more game features, a reward system, and an evaluative aspect.

Teachers said:

‘I'd have liked to have access to what they're writing.’

‘If the teacher can then put some feedback on there and then email it, that would be really useful.’

‘It's great for starting students, but the ones that can already do that need extension and more flexibility.’

‘I really love the idea of earning points, and someone suggested writing a sentence and people can vote. You could earn points and have a competition of who has written the best sentence starter.’

Limitations

Unavoidable limitations when conducting research in school settings include:

- unpredictable events

- absences

- time restrictions.

In this study, time restrictions affected the length of the writing task and the number of training sessions the students received. Although NAPLAN marking criteria provided an ecologically relevant measure, it is designed to rate students with a broad range of abilities and appeared to be insufficiently sensitive to detect small within-participant changes. Some schools had limitations such as insufficient numbers of iPads and access to wifi.

Meet the researchers

Professor Suzanne Carrington

Professor Suzanne Carrington

Professor Peta Wyeth

Dr Jill Ashburner

Dr Anne Ozdowska

All researcher details including names, honorifics (for example ‘Dr’), and organisational affiliations are correct at the time of the project.

Publications from this project

Ozdowska, A., Ashburner, J., Wyeth, P., Carrington, S. & Macdonald, L. (2018). Overcoming difficulties with written expression: Full Report. The Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC). Available on the Autism CRC website.

Ozdowska, A., Ashburner, J., Wyeth, P., Carrington, S. & Macdonald, L. (2018). Overcoming difficulties with written expression: Executive Summary. The Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC). Available on the Autism CRC website.

Articles informing this project

Allen-Bronaugh, D. (2013). The effects of self-regulated strategy development on the written language performance of students on the autism spectrum: George Mason University.

Asaro-Saddler, K. (2016). Using evidence-based practices to teach writing to children with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60(1), 79-85.

Asaro-Saddler, K., & Bak, N. (2012). Teaching children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders to write persuasive essays. Topics in Language Disorders, 32(4), 361-378.

Asaro-Saddler, K., & Bak, N. (2014). Persuasive writing and self-regulation training for writers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Special Education, 48(2), 92-105.

Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., & Pennington, A. (2012). The introduction of keyboarding to children with autism spectrum disorders with handwriting difficulties: A help or a hindrance? Australasian Journal of Special Education, 36(1), 32-61.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2017). Australian Curriculum Glossary. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabil….

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (2013). NAPLAN 2013 Persuasive Writing Marking Guide, ACARA, Sydney.

Beversdorf, D. Q., Anderson, J. M., Manning, S. E., Anderson, S. L., Nordgren, R. E., Felopulos, G. J., & Bauman, M. L. (2001). Brief report: Macrographia in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 97-101.

Bouck, E. C., Meyer, N. K., Satsangi, R., Savage, M. N., & Hunley, M. (2015). Free computer-based assistive technology to support students with high-incidence disabilities in the writing process. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59(2), 90-97.

Broun, L. (2009). Take the pencil out of the process. Teaching Exceptional Children, 42(1), 14-21.

Brown, H. M., Johnson, A. M., Smyth, R. E., & Cardy, J. O. (2014). Exploring the persuasive writing skills of students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(11), 1482-1499.

Burton, C. E., Anderson, D. H., Prater, M. A., & Dyches, T. T. (2013). Video self-modeling on an iPad to teach functional math skills to adolescents with autism and intellectual disability. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28(2), 67-77.

Cartmill, L., Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J. (2009). Handwriting of eight-year-old children with autistic spectrum disorder: An exploration. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 2(2), 103-118.

Center for Applied Special Technology. (2015). What is UDL. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/whatisudl

Charlop-Christy, M. H., Le, L., & Freeman, K. A. (2000). A comparison of video modeling with in vivo modeling for teaching children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(6), 537-552.

Cihak, D. F. (2011). Comparing pictorial and video modeling activity schedules during transitions for students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 433-441. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.006

Cochrane, D. P. (2012). Recontextualizing the Student: Analysis of the SETT Framework for Assistive Technology in Education. (Doctoral dissertation).

Cologon, K. (2013). Inclusion in education: Towards equality for students with disability (Issues paper). Children and Young People with Disability Australia.

Denning, S. B. & Moody, A.K. (2013). Supporting students with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive settings: Rethinking instruction and design. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 3(1), 1-19. Retrieved from https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=11…

Dillon, G., & Underwood, J. (2012). Computer mediated imaginative storytelling in children with autism. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 70(2), 169-178.

Dockrell, J. E., & Connelly, V. (2009). The impact of oral language skills on the production of written text. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 2(6), 45-62.

Evmenova, A. S., Graff, H. J., Jerome, M. K., & Behrmann, M. M. (2010). Word prediction programs with phonetic spelling support: Performance comparisons and impact on journal writing for students with writing difficulties. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 25(4), 170-182.

Feder, K. P., & Majnemer, A. (2007). Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(4), 312-317.

Given, L. M. (2008). Purposive Sampling. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (1st ed.). ProQuest Ebook Central: Sage Publications, Inc.

Glaser, C., & Brunstein, J. C. (2007). Improving fourth-grade students' composition skills: Effects of strategy instruction and self-regulation procedures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 297.

Grace, N., Enticott, P. G., Johnson, B. P., & Rinehart, N. J. (2017). Do handwriting difficulties correlate with core symptomology, motor proficiency and attentional behaviours? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(4), 1006-1017.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., MacArthur, C. A., & Schwartz, S. (1991). Writing and writing instruction for students with learning disabilities: Review of a research program. Learning Disability Quarterly, 14(2), 89-114.

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105-112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Green, D., Baird, G., Barnett, A. L., Henderson, L., Huber, J., & Henderson, S. E. (2002). The severity and nature of motor impairment in Asperger's syndrome: A comparison with specific developmental disorder of motor function. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(5), 655-668.

Harbinson, H., & Alexander, J. (2009). Asperger syndrome and the English curriculum: Addressing the challenges. Support for learning, 24(1), 11-18.

Harris, K. R., Graham, S., Friedlander, B., & Laud, L. (2013). Bring powerful writing strategies into your classroom! Why and how. The Reading Teacher, 66(7), 538-542.

Harris, K. R., Graham, S., & Mason, L. (2002). POW plus TREE equals powerful opinion essays. Teaching Exceptional Children, 34(5), 74-77.

Hasbrouck, J., & Tindal, G. A. (2006). Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers. The Reading Teacher, 59(7), 636-644. doi:10.1598/rt.59.7.3

Hasselbring, T. S., & Glaser, C. H. W. (2000). Use of computer technology to help students with special needs. The Future of Children, 102-122.

Hetzroni, O. E., & Shrieber, B. (2004). Word processing as an assistive technology tool for enhancing academic outcomes of students with writing disabilities in the general classroom. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(2), 143-154.

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165-179.

Johnson, B. P., Phillips, J. G., Papadopoulos, N., Fielding, J., Tonge, B., & Rinehart, N. J. (2013). Understanding macrographia in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(9), 2917-2926.

Jones, D., & Christensen, C. A. (1999). Relationship between automaticity in handwriting and students' ability to generate written text. Journal of educational psychology, 91(1), 44.

Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, N. L. (2004). Kaufman brief intelligence test - Second edition (KBIT-2). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Kay, R. H. (2014). Developing a framework for creating effective instructional video podcasts. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 9(1), 22. doi:10.3991/ijet.v9i1.3335

Kushki, A., Chau, T., & Anagnostou, E. (2011). Handwriting difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1706-1716.

Langone, J., & Levine, B. (1996). The Differential effects of a typing tutor and microcomputer-based word processing on the writing samples of elementary students with behavior disorders. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 29(2), 141-169.

Larsen, S. C., & Hammill, D. D. (1989). Test of Legible Handwriting. In J. J. Kramer & J. C. Conoley (Eds.), The eleventh mental measurements yearbook. Austin, Texas, USA: PRO-ED.

MacArthur, C. A. (2009). Reflections on research on writing and technology for struggling writers. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 24(2), 93-103.

Maeland, A. F. (1992). Handwriting and perceptual-motor skills in clumsy, dysgraphic, and ‘normal’children. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 75(3_suppl), 1207-1217.

Mason, L. H., Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2011). Self-regulated strategy development for students with writing difficulties. Theory into Practice, 50(1), 20-27.

Mesibov, G. B., & Shea, V. (2011). Evidence-based practices and autism. Autism, 15(1), 114-133. doi:10.1177/1362361309348070

Nikopoulos, C. K., & Keenan, M. (2004). Effects of video modeling on social initiations by children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37(1), 93-96.

Nippold, M. A., Ward-Lonergan, J. M., & Fanning, J. L. (2005). Persuasive writing in children, adolescents, and adults: A study of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic development. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36(2), 125-138.

Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284-299.

Robson, C., Blampied, N., & Walker, L. (2015). Effects of feedforward video self-modelling on reading fluency and comprehension. Behaviour Change, 32(1), 46-58.

Santangelo, T., Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2008). Using self-regulated strategy development to support students who have “trubol giting thangs into werds”. Remedial and Special Education, 29(2), 78-89.

Scaife, M., Rogers, Y., Aldrich, F., & Davies, M. (1997). Designing for or designing with? Informant design for interactive learning environments. Paper presented at the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Schneider, A. B., Codding, R. S., & Tryon, G. S. (2013). Comparing and combining accommodation and remediation interventions to improve the written-language performance of children with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28(2), 101-114.

Schultz, P. L., & Quinn, A. S. (2013). Lights, camera, action! Learning about management with student-produced video assignments. Journal of Management Education, 38(2), 234-258. doi:10.1177/1052562913488371

Semel, E., Wiig, E., & Secord, W. (2003). Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals, fourth edition (CELF-4). Pearson Clinical Assessment. Toronto, Canada: The Psychological Corporation/A Harcourt Assessment Company.

Sessions, L., Kang, M. O., & Womack, S. (2016). The neglected “R”: Improving writing instruction through iPad apps. TechTrends, 60(3), 218-225.

Sherer, M., Pierce, K. L., Paredes, S., Kisacky, K. L., Ingersoll, B., & Schreibman, L. (2001). Enhancing conversation skills in children with autism via video technology: Which is better,“self” or “other” as a model?. Behavior Modification, 25(1), 140-158.

Shute, V. J., D'Mello, S., Baker, R., Cho, K., Bosch, N., Ocumpaugh, J., . . . Almeda, V. (2015). Modeling how incoming knowledge, persistence, affective states, and in-game progress influence student learning from an educational game. Computers & Education, 86, 224-235. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.08.001

Stevenson, N. C., & Just, C. (2014). In early education, why teach handwriting before keyboarding? Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(1), 49-56.

Stewart, D., Shamdasani, P., & Rook, D. (2007). Focus groups. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.

TextHelp Ltd. (2015). TextHelp. Retrieved from http://www.texthelp.com/UK

Thomas, K., & Muñoz, M. A. (2016). Hold the phone! High school students' perceptions of mobile phone integration in the classroom. American Secondary Education, 44(3), 19-37.

Tracy, B., Reid, R., & Graham, S. (2009). Teaching young students strategies for planning and drafting stories: The impact of self-regulated strategy development. Journal of Educational Research, 102(5), 323-332.

Wallen, M., Bonney, M.-A., & Lennox, L. (1996). The handwriting speed test. Newington, Australia: Helios Art and Book Co.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Zabala, J. S. (1995). The SETT Framework: critical areas to consider when making informed assistive technology decisions. Paper presented at the Florida Assistive Technology Impact Conference and Technology and Media Division of Council for Exceptional Children, Orlando, FL.

Zabala, J. S. (2005). Using the SETT framework to level the learning field for students with disabilities (Revised) (pp. 1-4.).

Zhan, S., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2001). Single subject research designs for disability research. Disability & Rehabilitation, 23(1), 1-8.

Practices

Use technology to support written expression

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- express ideas

- develop written expression

Supporting persuasive writing

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- write persuasive texts

- organise thoughts

- work independently

Supporting handwriting

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- Build handwriting skill

- Maintain motivation